As you might guess, it’s my passion to search out models and frameworks that can make a lasting impact on early stage innovators. As someone who’s lived the creative, energy-charged, dynamic ride of being on the startup journey, I learned early on the importance of mental models to make order out of chaos. I used many of the frameworks that are now hallmarks of the WKI methodology inside the six startups I was fortunate to work with.

Competition is one of those areas where innovators and founders can use guidance – there’s just something about acknowledging competition that bristles the fibers of a founder. Yet we know that acknowledging competition and the position in the market shows a level of maturity vital to a founder transitioning from founder to leader. An effective approach I recommend is to put a design framework at the center of this conversation. One framework I introduce early and often is The Law of the Ladder – the formative work of Al Ries and Jack Trout, authors of the seminal book, “Positioning”.

It’s a simple, yet powerful mental model that structures an otherwise emotion charged conversation. It’s based on a few key principles:

- For each product category, there is a ladder in the customer’s mind. On each rung is a product name. A simple example would be mobile devices – Apple iPhone, Samsung Galaxy, Google Pixel. (Remember, this is the buyer/customer ladder).

- How many rungs are on the ladder depends upon whether the product category is high interest or low interest. This means how much time people devote to thinking about the purchase. As a rule of thumb, there are typically three rungs and perhaps as many as six, depending of course on how the customer evaluates products in the category.

- You typically have 50% of the market share of the product above you on the ladder and twice as much as the rung below you. The top two rungs typically dominate unless it’s a low interest category in which case the market divides itself out among competitors.

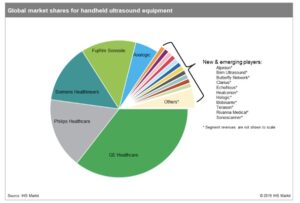

Here’s an example of the portable ultrasound product category. Look at the market share diagram below – GE Healthcare is the obvious top rung, followed by Philips, then Siemens. Worth noting, are the numerous emerging players looking to get a spot on the already occupied ladder. This is where strategy comes into play –how do the emerging players use their differentiators, business models, path to market, etc. to win spot on the ladder.

(A note: if your innovators/founders do not have knowledge of their competitors, the first step is to gather the facts. Data on virtually all product categories and competitors exists online and is available as evidenced by the portable ultrasound example below. Competitor due diligence is a skill that needs to be part of a founder’s DNA).

Here’s how I use the ladder framework with innovators (keep in mind we are building a foundation here):

- Start by identifying the product category where the idea sits. Then list out the various names of competitors working in and around the category.

- Think about the buyer next – when they think about buying products like this, how many different options do they consider? Now draw a ladder with this number of rungs.

- Find the market leader – the one company that is leading the pack. There is one (or two) in every market. This will take some discussion – you’re looking for the market leader not the technology Look also for #2 – they typically, as Ries points out, got their #2 position by being the exact opposite of the #1 market leader – i.e. Starbucks entering the market against Dunkin Donuts.

- Next, look at the others – are there any standing out ahead of the pack – do they have more market traction than the others. Do some fact gathering to determine which of the remaining competitors merit a spot on the ladder.

Once you have a ladder populated, there are various ways to advance the mindset of the founder/innovator about the competitive landscape:

- First, coaching founders to be able to speak objectively about competitors is a critical step. I’m a big fan of focusing on differentiators here – what’s different about each competitor and how does the founder’s product stand out as different from each of them. This takes the temperature down considerably when discussing competition.

- How many rungs are on the ladder? This tells you a lot about the buyer decision process. Don’t get caught here – don’t add rungs simply because there are companies to add – it’s all about how buyers make decisions. Recall the portable ultrasound case study.

- For an early stage startup, they may not even be on the ladder. How do they plan to climb on to the ladder and dislodge an incumbent? What will this take? Can you “outflank” one of them by improving on their main differentiator?

- There’s always a danger of founders saying they are the only ones on the ladder – “there’s no one doing what they’re doing”. This might be because the category they’ve identified doesn’t exist or is too small to be legitimate. Even if they are bringing a disruptive idea to market, there’s always competition – look at the adjacent categories in the market or the alternative ways the problem is solved today to determine who should be on the ladder.

There’s a clarity and confidence that comes from organizing the competitive discussion using a ladder. Plus, it focuses and prioritizes the true competition the founder should be watching. In the end, I like to believe we are equipping founders with foundation skills they carry with them to build their businesses.

If you coach or advise founders and entrepreneurs, I hope you try this out. It has been a difference maker for me to change the conversation about competition.

To learn more about Al Ries and Jack Trout’s work, go here: https://www.ries.com/articles/